Bands

Blind Faith 68-69

Born Under a Bad Sign

Mojo Magasine - by Johnny Black

IN THE EVENING COOL OF JUNE 6, 1969, almost 7,000 people made their way to Hyde Park. where they slept under stars to be sure of the best places in the natural amphitheatre of The Cockpit for the public wetting of a baby’s head.

The next morning dawned bright, and by lunchtime the weather was perfect for the 100,000 curious attendees of the christening.

The baby had been born a shade prematurely but to proud parents. They’d named it Blind Faith. Mr Eric Clapton and Mr Steve Winwood had simply wanted to make something good together and their union had seemed a match made in heaven. The young couple, both recently divorced, got along famously, respected each other’s talents and, best of all, each supplied what the other had lacked in his previous relationship. Steve had the voice and keyboard talents while Eric had the guitar side pretty well taped.

It should have been The Golden Child but, instead, it was Rosemary’s Baby.

CLAPTON AND WINWOOD HAD KNOCKED AROUND together for years. While Clapton was still God, playing with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, he frequently turned out to jam with Winwood during The Spencer Davis Group’s Thursday night residency at London’s Marquee Club in 1966. The pair would also get together whenever possible at blues festivals and even appeared on record as Powerhouse, a short—lived studio—only combo which had contributed several tracks to What's Shakin', a blues-boom cash-in compilation.

The possibility of working together in a full-time band, however, seemed remote. Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, The Yardbirds and Cream kept Clapton busy and, after the demise of The Spencer Davis Group, Winwood was more than fully occupied with Traffic. By the middle of 1968, however, neither man was happy with his lot.

“In Cream, there was a constant battle between Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce,” explained Clapton later. “They loved each other’s playing, but they couldn’t stand the sight of each other. I was the mediator and I was getting tired of that.” And, when Clapton conveyed these feelings to the band’s manager, Robert Stigwood,the response was comforting.

If Cream split, Stigwood assured him, Clapton was the one he would stick by. Even so, Clapton was not yet ready to quit. Cream had one foot in the grave but he felt the band might yet return to rude health if only Steve Winwood could he brought in on keyboards. “I’d heard the tapes of Music From Big Pink by The Band and I thought, this is what I want to play not extended solos and maestro bullshit but just good funky songs.”

Clapton reasoned that Winwood’s presence might stabilise the group by adding an element of song composition and a shift of emphasis towards vocals, rather than the endless instrumental improvisation which Clapton now found so tiresome.

But before Clapton could approach Winwood, the final nail was knocked into Cream’s coffin. “Rolling Stone called me ‘the master of the cliché’ which just about knocked me cold. At that point, I decided to leave Cream.” Destroying a hand because of the opinion of a single journalist might seem drastic, but Ginger Baker confirms that Rolling Stone was Clapton’s bible. "As soon as he got it, he would read it from cover to cover. From the day he saw that review he wanted to be in the background. He didn’t want to be the focus of attention any more.”

By the time Cream played its farewell concerts at the Royal Albert Hall on November25 and 26, 1968, Clapton and Winwood had begun their first tentative steps towards working together. Although still a member of Traffic, Winwood spent that Christmas with Clapton at his home, Hurtwood Edge, where they jammed long into the night. “When I left Traffic in January, I knew I was going to work with Eric,” says Winwood.

“We’d talked about it for ages. He’d just quit Cream and I’d gone through a lot of changes with TraffIc, and we were keen to do something.” Drummer Jim Capaldi remembers Winwood’s departure from Traffic as a bolt from the blue. “He just split. I don’t know what happened. He never said why, he never said he was splitting. We found out from Chris Blackwell.”

Aside from such lingering resentments from their old bands, the prospects looked good but, insulated from the harsh realities of the music business by their status, neither Clapton nor Winwood could see that the seeds of their destruction were already sown. Robert Stigwood, keeping his promise, was now overseeing Clapton’s career.

Similarly as a legacy from the days when Island Record's boss Chris Blackwell had found and nurtured The Spencer Davis Group, Winwood was under his management wing. For his shrewdness in making deals, Ahmet Ertegun, founder of Atlantic Records, dubbed Old Harrovian Blackwell “the baby- faced killer”.

Today, with his wallet bulging to the tune of £110 million, he ranks as the 145th richest man in Britain, a position shared with Mick Jagger. Stigwood, an Australian immigrant who’d arrived in Britain nearly penniless, then guided Cream and The Bee Gees to success, is now ranked 96th with a personal fortune of around £160m.

Back in 1969, their combined financial might was already impressive but, unfortunately, according to former Pink Floyd manager Andrew King of Blackhill Enterprises: “As far as anyone could make out, Stigwood and Blackwell absolutely despised each other. They had different priorities.

Chris was devoted to Stevie and Stigwood was devoted to his cheque book.” Winwood denies knowledge of any animosity between the management duo: “I’ve no idea what their personal relationship was, but in a business sense it almost certainly wasn’t to our benefit. It never came to fights between us and them, but they wanted a supergroup and we didn't."

Clapton has put it rather more strongly: “I can see now that we were very foolish to have two managers, but our relationship with Stigwood went back to my days in The Graham Bond Organisation. I realise now that he took advantage of my trust in him — even in Blind Faith we didn’t have a good deal financially. I think that if Blackwell had managed the whole band, we might have survived.”

BY THE BEGINNING OF 1969, THE MUSIC PRESS WAS speclating that Clapton and Winwood might form a band, but early guesses about the rhythm section went wide of the mark because during Cream’s farewell tour, Clapton had suggested to Al Jackson and Duck Dunn, legendary rhythm section of Booker T And The MGs, that he might like to work with them.

Anxious to keep the project low-key Clapton told Melody Maker that any new group might be short-lived, possibly even a stopgap until Cream re-formed with Winwood on board. He added that his real intent was to “drop out of it completely, publicity wise, press wise.”

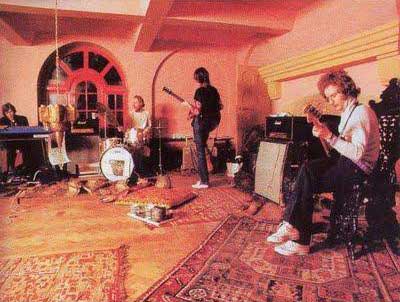

Meanwhile, rehearsals continued at Winwood’s cottage in Berkshire throughout a cold February. Feeling that Winwood had the better voice, Clapton continually encouraged him to take most of the limelight. That March, Ginger Baker drove down to Hurtwood Edge only to find Clapton on his way out to Berkshire. Ever sociable, Clapton invited Ginger along although, as he later put it, “I love Ginger very much but, at that time, I didn’t really want him around.”

“We got to Stevie’s cottage in the middle of a field, and I settled down at Jim Capaldi’s drumkit and we just played for hours,” remembers Baker. “Musically, Stevie and I got along wonderfu11y. He was one of the greatest musicians I’ve ever worked with.

“What I didn’t know then was that Eric would probably rather have worked with Jim Capaldi. It’s a curious thing with me and Eric. I regard him as the nearest thing I’ve got to a brother, but we always found it difficult to talk about personal things. He never explained, for example, that he wanted it all to be a much more low-key affair than Cream had been.”

“I had to convince Eric to let Ginger join,” explains Winwood. “we'd played together before and he was someone I really respected as a drummer and enjoyed working with. It wasn’t until later that I realised how much Cream had been built round the interaction of Ginger and Eric. I knew Ginger did serious drugs but I didn’t realise how destructive that could be, because I’d never encountered it before.”

As he had done in Traffic, Winwood was playing bass lines on his organ but it was obvious that, to have complete freedom to play at his best, a bass player was required. Clapton had admired Rick Grech, bass player for Leicester art-rockers Family, since the days when that band was known as The Farinas: “I knew he was a good singer and could play great, and that was the guy we wanted.” Winwood: “We didn’t even consider any other bass players. Once Rick was around, and he seemed like a nice guy it was just very casually accepted that he was in the band.”

Ginger and Rick were now on board but, publicly, Clapton remained evasive. “We’re just jamming and we have no definite plans for the future,” he told NME, even though recording sessions were already under way in Morgan Studios with Chris Blackwell at the desk.

As first sessions often do, this one started badly with everybody taking hours to set up. Then, fortuitously, former Moody Blues vocalist Denny Lane walked in and picked up a guitar. “We all started playing along with him, and he completely lifted the mood,” recalls Baker.

“We did a fantastic jam that day but Blackwell didn’t bother to record it. I blew up at him, and Jimmy Miller took over the next clay.” Baker makes light of his studio outburst, but DJ Jeff Dexter who was there that day vividly recalls Baker grabbing a microphone from the front of his drum kit and screaming out a torrent of abuse that continued for what felt like 15 minutes.

“If the tape Op who forgot to switch the machine on had walked into the studio, Baker would have torn him limb from limb,” reckons Dexter. “After about five minutes there were girls crying and people were leaving the studio to get away from him. It was as if the room was reverberating with it.”

Otherwise, the sessions, under Jimmy Miller, provided one of the few periods of relative calm in Blind Faith’s troubled history. “They were full of people hanging out,” says Winwood. “Eric had a lot of bohemian friends and liked to record with people around. The only thing I remember not being very pleased with was Can’t Find My Way Home. It was only when I heard it again later that I realised how good it was.”

In the wake of Cream, the notion of all-star jamming “supergroups” was in the air. There had been the Super Session album featuring Stephen Stills, Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper. The Rolling Stones’ Rock’N’Roll Circus had brought together Lennon, Clapton, Tull, The Who and more.

The TV special Supershow featured Clapton, Stills, Led Zeppelin and Buddy Miles. Perhaps even more significantly, Crosby, Stills And Nash were already one album down the line and planning a tour. “Gradually, Clapton and I were both becoming acutely aware of the hype building up,” says Winwood now.

“The industry was waking up to the fact that The Beatles There was the clear possibility that other bands could achieve similar things. They could see spin- offs, merchandising, slices of pie to be had. It was the dawn of corporate rock and we were among the first victims. That’s why we wanted to start off with a free concert, to show that we weren’t part of that corporate business mentality.”

Before April was out, the rock press reported that the as-yet-nameless combo would debut in Hyde Park, at a free concert on June 7, and would tour Scandinavia later in the year. “Never was there a moment to develop the character of the band,” reflected Winwood years later. “Who would let a million-dollar-a-week pontential in a band sit around and rehearse? The management and the record company joined our own greed. There was a multi—million dollar time bomb out there.”

In fact, there was more than one time-bomb. Although Rick Grech was now a member of Blind Faith, he neglected to menbon this fact to the other members of Family. Roger Chapman, Family’s vocalist, remembers: “The first inkling I got that Rick might be leaving was when I read an interview in a rock paper where Jimi Hendrix was asked why he thought bands changed.

He said, ‘People have got to move on, these bands split, like Family.’ Obviously, Rick had told him and hadn’t told us. The rumours are flying and these four berks at the back know nothing about it.”

Grech waited for an American tour to drop his bombshell. “He should have fucking left before the tour started,” says Chapman. “He and Gilbert [John Gilbert, Family’s manager] obviously knew before we got to America. They didn’t tell us until the day before we opened at the Fillmore East, where we died. Then we had all our equipment nicked in New York, and I lost my passport and it all sort of fizzled out.” It was the beginning of the end for Family; it was also the beginning of the end for Grech’s new band.

A NAME HAD BEEN CHOSEN — BLIND FAITH. “I KNEW IT WAS a hype as soon as it was called Blind Faith,” says Winwood. “I think the name was largely Eric’s idea, but I felt it had certain negative implications. I went along with it only because, after a while, if a band is successful, the name loses its meaning and just becomes a label.”

June 7, 1969 was a scorcher. By the time Blind Faith got to Hyde Park the crowd was 100,000 strong. Jagger and Faithfull were backstage, as were Donovan and Mick Fleetwood, along with former Traffic members Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood. “Stigwood stood out like a sore thumb at the gig,” recalls Andrew King, whose Blackhill Enterprises promoted the event. “For a start, he was the only man there in a suit, a very stylish dark blue job it was. What rather spoiled the image was that the shoulders were absolutely covered in dandruff.”

The inevitable Third Ear Band took the stage at 2.3Opm for their woozy brew of sitars, tablas, strings and oboes, followed by The Edgar Broughton Band (also obligatory at outdoor events in 1969). There was a brief foretaste of Woodstock from Richie Lavens, an unannounced spot by Donovan, inaudible to the majority of the crowd but well-received by the throng at the front, then, with the heady sweet aroma of dope wafting on pale blue clouds from the audience, Blind Faith took the stage at 5pm. Kids clambered on car roofs and shinned up trees for a better look as the opening chords of Buddy Holly’s Well All Right blasted out.

We had basically the same set—up we’d have used if we were playing to a hall with 3,000 people in it,” points out Winwood. “We didn’t have experience yet of big outdoor gigs. It was our first gig and to do it in front of 100,000 people was not the best situation. Nerves were showing and it was very daunting. couldn’t relax.” In an attempt to lighten the mood, Baker announced, “This is the first rehearsal.” Clapton, in jeans and T-shirt, and using a Fender Telecaster with a Strat neck, lingered in the shadow of his Marshall stack, delivering only one memorable solo, in I’d Rather See You Sleeping On The Ground.

Baker, still evidently in Cream mode, was tending to push the band too hard. “This was when I first noticed something was amiss,” he says. “In rehearsals, and during recording, Eric bad been doing amazing stuff but in Hyde Park I kept wondering when he was going to start playing.” Rick Grech, who had the least experience of larger gigs, simply kept his head down and ploughed on: “I was nervous,” he said afterwards. “Everybody was. We knew the numbers, but not to the extent of not having to think about them.” Clapton remembers how; even after three encores, “I came off stage shaking like a leaf because I felt, once again, that I’d let people down.”

Cries of “We want the Cream back” rang out from disappointed die-hards and the subdued nature of the crowd as they drifted quietly out of Hyde Park can only have reinforced Clapton’s dismay. Stigwood, seemingly oblivious to the muted response, continued to trumpet great things both for the unwilling supergroup and himself: “They are going to make a lot of money in appearance and on records, and this concert was the best possible beginning. I am going to make a great deal of money out of it from the film and television rights all over the world.”

Immediately after Hyde Park, the band flew off for the Scandinavian tour and it was not until their return that they could check the reviews. Seeing mainly criticism of their reliance on Winwood’s voice and keyboards, which Clapton himself had insisted on, they turned their thoughts towards America, where they would shortly embark on one of the first stadium rock tours ever, supported by Island label colleagues Free and little known American Southern rockers Delaney and Bonnie.

Tour manager Ben Palmer remembers that the rest of Blind Faith flew from gig to gig but Clapton travelled with Delaney And Bonnie, “scrambling into the bus with all the enthusiasm of somebody in their first Bedford Dormobile going off to the Ricky Tick club. We didn't see half of him, except when it was time to go on. Travelling had become such a disjointed affair that the whole entourage would be spread over hundreds of miles rather than everybody travelling together. Not because there was any friction, but just because there was no point. It wasn’t alive; it never lived at all.”

THE SPECTRUM IN PHILADELPHIA ON THE 16TH BROUGHT cheer in the form of a much better show. “I’m very pleased,” reported Clapton after the gig. “I feel good. This is a new group. This isn’t the Cream — it’s four different people playing music. By the end of this tour we’ll be four individual musicians and each of us will be known for what we can do on stage.” For Winwood, unfortunately by the time they hit Baltimore, “I had begun to realise what a problem Ginger was and I saw why Eric had been against having him in the group.”

Even the American release of the album on July 21 with staggering advance orders of 250,000 guaranteeing an instant Number 1, turned out to be a silver cloud with a black lining. On seeing the album cover, featuring a naked pre—pubescent girl holding a somewhat phallic silver aeroplane, almost 70 per cent of US dealers cancelled their orders.

Winwood can’t have been surprised, having hated the sleeve from the beginning but, once again, he’d gone along with the general feeling that it was right for the band. In the hilarious public debate that followed, Rick Grech suggested that the sleeve represented “a contrast between and innocence and the great scientific progress of the day” Photographer Bob Seidemann elaborated Grech’s line, explaining that, “The virgin with no responsibility is the fruit of the tree of knowledge. As man steps into the galaxy, I want innocence to carry my spaceship.” But somehowRobert Stigwood’s explanation ‐ “It doesn’t mean anything. We just liked the design”— is the one that rings true.

The real dilemma, of course, had nothing to do with artistic merit or moral outrage. It was about seeing record sales go up in smoke. Ahmet Ertegun, head of Atlantic Records, quickly cobbled together a damage limitation strategy “We do not agree that the original sleeve is offensive,” he told the press, “but if any dealers do not want that cover we will happily supply them with an alternative.” A shot of the hand was switched from back cover to front; a note inside told purchasers who wanted the original sleeve to write to Atlantic. The original was soon back on sale with a ‘Collector’s Edition’ sticker strategically covering the maiden’s not terribly naughty bits.

A week later, as the tour rumbled on, up into Canada then back down again into Milwaukee, the album was confirmed gold. “Koss [Paul Kossoff, guitarist with Free] was totally in awe of Clapton, and we were all thrilled to be on the same tour as them,” remembers Simon Kirke, “but it was two weeks on the road before we actually met any of them. Steve Winwood came to our hotel, somewhere in the Mid-west, and started talking about how much he envied our freedom to do what we wanted.”

Instead of doing what they wanted, Winwood and Clapton found themselves churning out Sunshine Of Your Love against their will, obliged to play much too loud simply in order to hear themselves above the screaming. “I didn’t have any control over it and, what was worse, everyone in the group felt differently about it,” remembers Winwood.

“I didn’t want to play coliseums. I was really fed up playing in those places and to those audiences. It was very false. We could play really terrible and get exactly the same reaction as if we’d really played fucking good. When it came down to it, we failed because we couldn’t resist requests for the hits. Ginger did a drum solo and they thought it was Cream, so we chucked in an old Cream song. Then I put in a Traffic song and the identity of the band was killed stone dead. If you have 20,000 people out there and you know you only have to play one song for them to be on their feet, you do it. We were only human.”

Towards the end of July there was a gap in the tour schedule to give Blind Faith a break, but as Simon Kirke recalls, “We couldn’t afford to stop working, so Chris Blackwell got us some dates at Lingaro’s in New York, sharing the bill with Dr John. One night our roadie said that Clapton and Baker were in the audience, which was amazing. Koss was knocked out, and he played his heart out. After the set, they came to our dressing room. Clapton made a bee-line for Koss and started asking how he achieved one of his effects, a particular kind of vibrato in the left band. If Koss could have died and gone to heaven that night, he’d have been a happy man.”

The tour resumed on August 1 at Detroit’s Olympia Stadium, after which a party was thrown for the band on an island in Lake Erie. “I was very late arriving,” says Baker, “but even when I got there, Eric was nowhere to be seen. I asked Steie where Eric was but he didn’t know ‘We just presumed he was with Delaney And Bonnie. It was obvious then that he had effectively left the hand.”

But, as Baker willingly concedes, Clapton was not the only member whose behaviour was causing problems. "As the tour went on, I got more and more heavily into the drugs again. I was flying the whole time. I think it was the way Eric was behaving that drove me into it. I was hurt by him spending all his time with Delaney And Bonnie but, of course, with me doing drugs, he hated the kind of people I was hanging out with. I became totally insensitive to what was going on around me, or to anybody else’s feelings.”

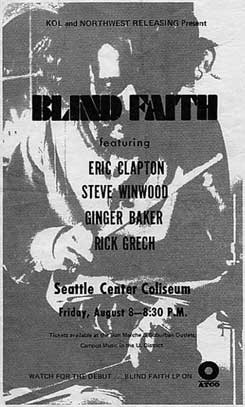

After the Seattle Center Stadium date on August 8, the tour swung up into Canada for a second time and Baker drove manager Chris Blackwdll through customs. “Chris had come out to New York at the start of the tour and bought himself a Pontiac Firebird. Then he went home and left me in charge of the car. He rejoined us just before Vancouver and after we cleared customs, I said, ‘Do you want to know what you’ve just brought in to Canada?’ He threw up his hands and said, ‘Please, Ginger, don’t tell me’.”

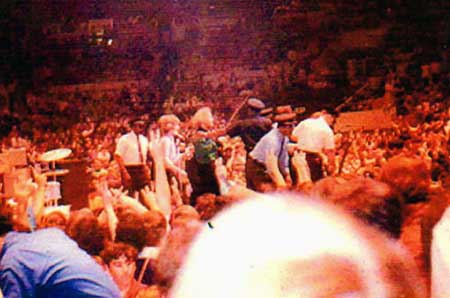

WHILE WOODSTOCK WAS ENJOYING THE FIRST OF THREE days of peace, love and music, Blind Faith arrived at the Los Angeles Forum. Evidently lacking any sense of the irony inherent in the band’s name, a huge hand-made ‘Clapton Is God’ placard was borne aloft by some fans. Word was out by now that Blind Faith gigs could be troublesome so, as soon as kids began to dance in the aisles, LAPD’s finest moved in with batons at the ready. The show was stopped twice as the house lights were turned on and fans were dragged out into the night. When a phalanx of kids surged towards the eight-foot-high stage, so many police formed a protective line along stage front that Clapton had to move to the rear of the platform. But the gig ended in triumph with Sunshine Of Your Love, peace signs flashing in their thousands.

However, word had reached the press that the band would soon split. At the post-gig reception in LA’s Forum Club, Rick Grech denied the rumours. “We’ll be together as long as things are good, and tonight they’re way up there,” he said. The same day the album was released in the UK with a gatefold sleeve, so that dealers could rack it inside-out to avoid offending customers.

The tour wound down through California and Texas with relatively little incident, but Simon Kirke vividly remembers Ginger Baker’s arrival at The Palace, Salt Lake City, on August 22. “It was blistering heat that night and Ginger was incredibly late for the gig. Everybody was getting nervous backstage that he wouldn’t show at all. He’d been out having some kind of birthday party. Suddenly there was this sound like a sledge-hammer battering on the big metal doors. The security guys opened up and in strides Ginger with a girl on each arm. He played a great show that night and there was a party for him afterwards in the hotel which he didn’t even attend. I guess he was upstairs with the girls.”

The disasters continued on August 23 at the Memorial Coliseum, Phoenix. “You could see there was going to be trouble even before the fighting started,” remembers Baker. “The police were total Nazis, with black jackboots and everything. They despised the likes of us because to them we were long-haired, drug-taking commies. When Eric tried to go on stage to play tambourine with Delaney And Bonnie, the cops hauled him off the stage. I’ve never seen Eric so angry.” The hall’s revolving stage broke down; half the crowd could see only the band’s backs. Road crew security men and support bands pushed it round manually.

“Delaney And Ronnie were having a hard time through lack of billing and weird contract and money scenes,” revealed Clapton years later. “Phoenix was their last night on the tour and, like most nights, we jammed with them. Bonnie got really into it and fell off the stage, down 10 feet onto concrete. Pandemonium broke out. The cops dragged her to an office and would not let us in. After arguments, we eventually got in and took her out with Delaney carrying her. There were more hassles with the cops and Delaney dropped her again onto the concrete and she ended up in hospital with a broken vertebrae.”

After a final, suitably triumphant gig on the 24th at the HIC Arena in Honolulu, the tour had cleared $900,000. The others flew home to catch Dylan at the Isle Of Wight, but Baker remained in Hawaii for 10 days, in serious need of rest and recuperation. It was exactly the wrong place to be because Hawaii was an important staging post on the heroin route from the Far East into America. “I was trying to cold turkey, but everybody around me was on drugs. I had to get out of there or I was heading for the graveyard.” He flew down to Jamaica and spent five more weeks cleaning up, then boarded a slow boat back to the UK via South America. What he still didn’t know was that Blind Faith no longer existed.

He was not alone. With the album at Number 1 in America, the NME reported on September 6 that Blind Faith was planning a European tour in the autumn. Clapton, as ever, remained tactful, telling NME on the 15th that “I am pleased with the album and with a lot of the performances we did, but I don’t think the group is going to stay together very long. Stevie is going to do something on his own and I will too.” By the end of month the album was also at Number 1 in the UK.

By the time they landed back in England, Winwood and Clapton had decided it was over. “We didn’t even have to talk the end of the band through,” recalls Winwood. “It was perfectly obvious to Eric and me on that tour in America that it couldn’t last. As we had put the band together, so we just split up. In fact, we didn’t split formally We just drifted away” In Clapton’s words: “I’d left The Yardbirds because of success, and Cream ended as a direct result of its false success, or what appeared to me to be a hypocritical form of success. So with Blind Faith, I wanted no more to do with success. I wanted to be accepted as a musician.”

Robin Turner, Clapton’s publicist in the ‘70s, has noted that, “He becomes different people. When he was with George Harrison a lot he bought a big house like George’s and a big Mercedes. When be was with Stevie Winwood and Blind Faith, he went back to jeans and wanting to live in the country. When he met Delaney And Bonnie he gave up travelling first class and just climbed into their bus.”

On June 29 1996, Eric returns to Hyde Park after a 27-year absence; Steve Winwood records a new album; Ginger Baker lives in Colorado, where he runs his Mile High Polo Club and records sporadically. Rick Grech, after working with Traffic, Clapton, The Crickets, Gram Parsons and KGB, dies in March 1990 of drug-related problems.

IN RETROSPECT, BLIND FAITH WAS CURSED ALMOST FROM the outset. This was a band whose members rarely seemed to tell each other anything. A band at loggerheads with its management. A management at loggerheads with itself. A heroin addicted drummer. A guitarist who wanted out almost from the word go. A stadium tour that the keyboard player didn’t want to be on. A record cover scandal. Worst of all, though, they were mind-numbingly successful when they didn’t want to be.

The final irony was soon forthcoming. With the band already a fading memory to its former members, a still blindly faithful public voted them Britain’s Brightest Hope in the Melody Maker Reader’s Poll.

Thanks and acknowledgement to Ray Coleman, Marc Roberty, Harry Shapiro, Steve Turner John Pidgeon, Pete Frame, Neil Storey, Nina Antonia, Jeff Dexter, Chris Welch, Mick Dillingham, Nick Logan, June Harris, Anthony De Curtis, Barbara Charone, Penny Stallings.

At the Hyde Park concert in 1969 ...

Alec Martin "I was there!! Travelled overnight on a bright blue 1940's double decker bus from Bolton... about 50 of us on board! Hit London 8am...all bowler hats flagging us down thinking we were London Transport (Bright blue and you could smell the dope and patchouli from about half a mile away :D Fell asleep during 3rd Ear Band... woke up and had a walk, saw Donovan 'busking' under a tree... (thought he was a really good impersonator at first, till we got close and saw it was really him!)"

At Maddison Square Gardens ...

Joe "Delaney and Bonnie, Free, and Blind Faith at MSG....Ginger was the first to walk on stage..took off his jacket, banged a stick off his tom, sat down caught the stick and played... the place went nuts... They played Cream songs, for me Sea of Joy was a show stopper, Rick's violin solo was great....Blind Faith was a great live band at the Garden... Blind Faith was a great band... and the album is a classic...

Thom "I was there, and it was way too scary. The house lights came on during the last song, and that's when chairs started to get knocked over. It reminded me a bit of seeing the Doors at the Singer Bowl, the previous summer. Way too dangerous. Nothing like that ever happened at the Fillmore East."

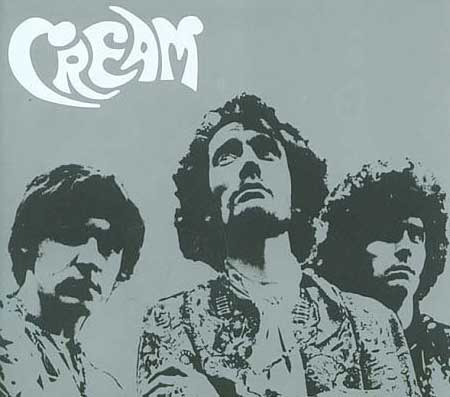

Cream 66-68

CREAM MYTHICAL BLUES GODS

by Howard Druckman

The virtuoso playing of Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker made Cream the first band of soloists. In their two year career they brought the blues to a whole generation of white rockers and spawned legions of power trios, boogie bands and heavy metal groups...

According to rock critic Dave Marsh, Cream created “the fastest, loudest, most overpowering blues-based rock ever heard, particularly onstage.” Though they lasted only two years, Cream sold 15 million records; earned the first certified platinum album in history (for the double set Wheels of Fire); played to standing-room-only audiences across Europe and North America; and redefined the instrumentalist’s role in rock.

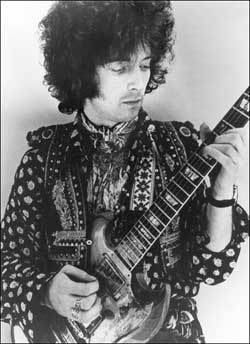

Indeed, the trio is often cited as the first “supergroup.” Eric Clapton’s passion and fluidity on guitar inspired a spate of “Clapton is God” graffiti in London; Ginger Baker’s brutal intensity helped create the tradition of the drum solo in rock; and Jack Bruce was one of the first bassists to introduce a jazz sensibility to a hard rock format.

Eric Clapton, born in March, 1945, was first inspired by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and later by Jerry Lee Lewis. He quickly graduated from a plastic guitar to a real one, and from small-town Ripley to cosmopolitan London. There, he immersed himself in the nascent British blues scene, playing in the Roosters and Casey Jones & the Engineers before achieving an axemaster’s reputation with the Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

In the last Bluesbreakers lineup, Jack Bruce was playing bass. He left to join Manfred Mann, but not before Clapton had become excited enough by his work to want to form a band. When drummer Ginger Baker, about to leave the jazz- tinged Graham Bond Organisation, asked Clapton if he wanted to start a band, the trio became inevitable. Despite animosity between Bruce and Baker, Cream was formed in July, 1966.

They made their debut at the 1966 Windsor Festival in England, and rapidly established their legendary live style — a combination of high-volume blues jamming, extended solos and flashy instrumental showmanship.

Their first album, Fresh Cream, was released in January, 1967, to moderate U.K. success. It included such chestnuts as Skip James’“I’m So Glad” and Muddy Waters’“Rollin’ And Tumblin’,” and like their live show expanded the possibilities of blues playing far beyond the traditional limits of slavish imitation. It also turned a legion of white rockers on to the sound, and in April, when it hit the U.S. charts, a host of followers — boogie bands, power trios and heavy metal groups — was spawned.

In the meantime, though, flower power, psychedelia and Jimi Hendnx were making their way across the Atlantic. Consequently, Cream’s second LP, Disraeli Gears, was filled with short, pungent rock originals drenched in fuzz-tone, wah-wah and other then-revolutionary guitar effects. It was released in December, 1967, and a few months later “Sunshine Of Your Love” reached number five on the U.S. charts. Spicy, sophisticated rockers like “Tales of Brave Ulysses” and “Swalbr” became FM underground radio staples. This was when Clapton’s comparisons to the Deity began, as he became the focus of the guitar cult that developed in the late ‘60s.

Naturally, success was accompanied by tension. Egos bloated, personalities clashed; when Bruce and Baker weren’t fighting amongst themselves — which wasn’t often — they complained of Clapton’s virtual domination of the band. There were also tensions between Clapton’s blues approach and the rhythm section’s jazz snobbery (it was almost inevitable that three overpowering improvisers would step on each other’s musical toes).

Offstage, Cream’s drug abuse was mythic. All three indulged in grass, acid and coke. Baker was using heroin heavily, and Clapton started dabbling down a road that would eventually lead him to a hard, isolated two-year heroin addiction.

Against this backdrop, Cream released Wheels of Fire in June, 1968. The album balanced short, clever songs like “White Room” (mostly written by Bruce and lyricist Pete Brown) with long blues jams like Willie Dixon’s “Spoonful” (mostly guitar workouts for Clapton).

The band gave final concerts in London and New York in November, 1968. In January, 1969, they released a post-breakup collection, Goodbye, with three old and three new songs. Among the new was “Badge,” a subtle but powerfully insistent pop song with a mellotron-treated guitar section courtesy of Angelo Misterioso, otherwise known as George Harrison. A live version of “Crossroads” brought a Robert Johnson blues song to number 28 on the U.S. charts in 1969.

Jack Bruce went on to jazz experimentation, and turned up on the Golden Palominos’ recent LP, Visions of Excess. Ginger Baker discovered Africa before it got cool, and moved there. He went through two bands, isolated himself to grow olives in Italy, and was last seen bashing the hell out of a drum kit on PIL’s recent Album.

Clapton went on to sessions with the Beatles; to the short-lived Blind Faith supergroup; to being a sideman with Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett; to a solo album; and then to Derek and the Dominoes, whose double album Layla offered the most exquisitely painful guitar pyrotechnics of his career. He periodically resurfaces, most recently with Phil Collins, but few would argue that his laid-back style matches the inspiration of his work with Cream.

Ginger Baker, meanwhile, insists that Cream will never re-form. Nevertheless, in these days of post-psychedelic revival, it’s not uncommon to hear Cream down at the dance club or the rock bar, where “Sunshine of Your Love” and “White Room” are being worked into the mix, sounding every bit as fresh as ever.